Expo

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

Clinical Chem.Molecular DiagnosticsHematologyImmunologyMicrobiologyPathologyTechnologyIndustry

Events

Webinars

- Extracellular Vesicles Linked to Heart Failure Risk in CKD Patients

- Study Compares Analytical Performance of Quantitative Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Assays

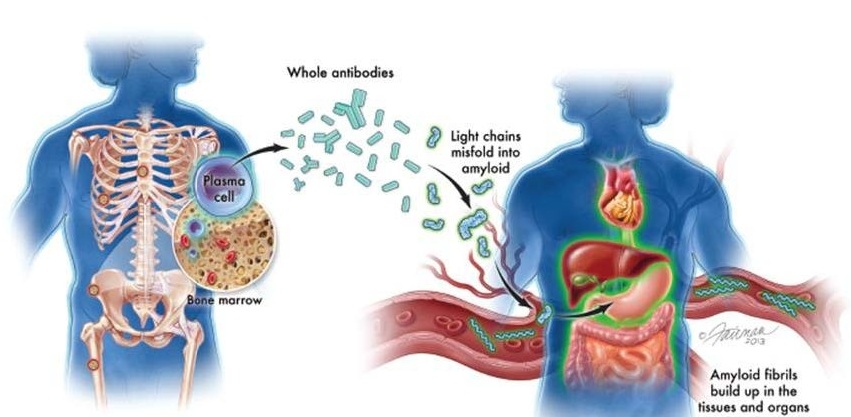

- Blood Test Could Predict and Identify Early Relapses in Myeloma Patients

- Compact Raman Imaging System Detects Subtle Tumor Signals

- Noninvasive Blood-Glucose Monitoring to Replace Finger Pricks for Diabetics

- Blood Test Detects Early-Stage Cancers by Measuring Epigenetic Instability

- “Lab-On-A-Disc” Device Paves Way for More Automated Liquid Biopsies

- Blood Test Identifies Inflammatory Breast Cancer Patients at Increased Risk of Brain Metastasis

- Two-in-One DNA Analysis Improves Diagnostic Accuracy While Saving Time and Costs

- Newly-Identified Parkinson’s Biomarkers to Enable Early Diagnosis Via Blood Tests

- Fast and Easy Test Could Revolutionize Blood Transfusions

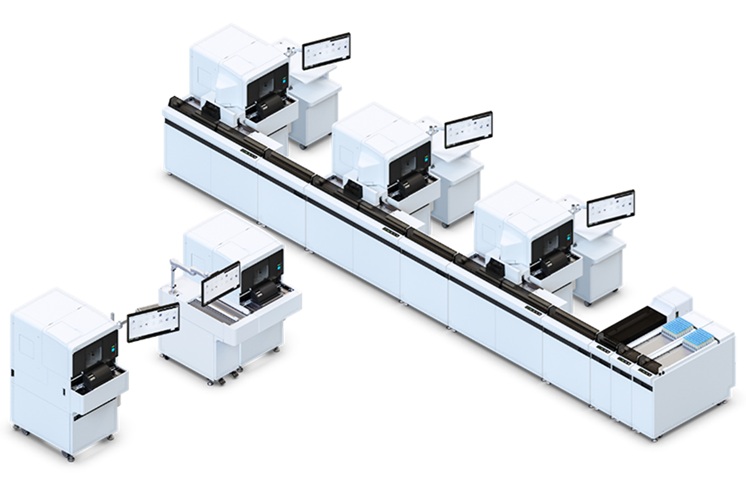

- Automated Hemostasis System Helps Labs of All Sizes Optimize Workflow

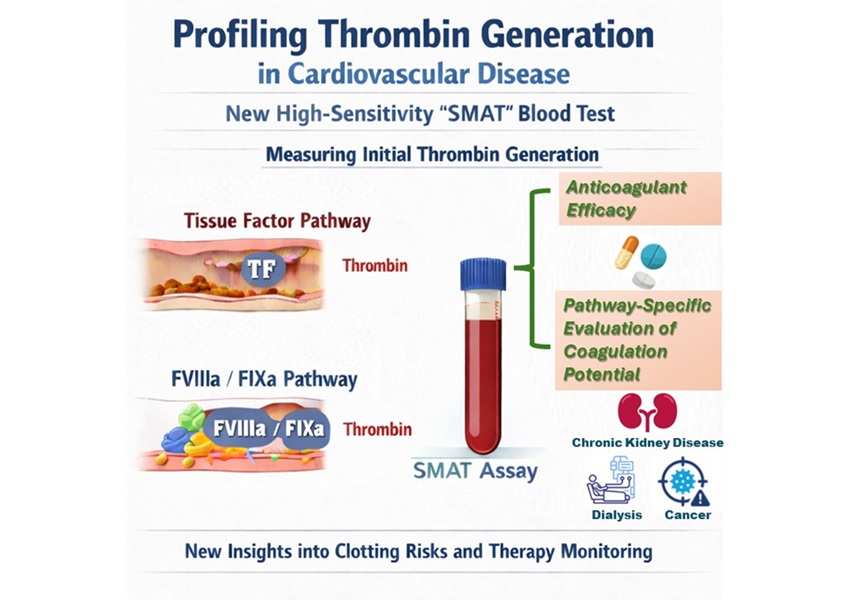

- High-Sensitivity Blood Test Improves Assessment of Clotting Risk in Heart Disease Patients

- AI Algorithm Effectively Distinguishes Alpha Thalassemia Subtypes

- MRD Tests Could Predict Survival in Leukemia Patients

- Whole-Genome Sequencing Approach Identifies Cancer Patients Benefitting From PARP-Inhibitor Treatment

- Ultrasensitive Liquid Biopsy Demonstrates Efficacy in Predicting Immunotherapy Response

- Blood Test Could Identify Colon Cancer Patients to Benefit from NSAIDs

- Blood Test Could Detect Adverse Immunotherapy Effects

- Routine Blood Test Can Predict Who Benefits Most from CAR T-Cell Therapy

- AI-Powered Platform Enables Rapid Detection of Drug-Resistant C. Auris Pathogens

- New Test Measures How Effectively Antibiotics Kill Bacteria

- New Antimicrobial Stewardship Standards for TB Care to Optimize Diagnostics

- New UTI Diagnosis Method Delivers Antibiotic Resistance Results 24 Hours Earlier

- Breakthroughs in Microbial Analysis to Enhance Disease Prediction

- ADLM Launches First-of-Its-Kind Data Science Program for Laboratory Medicine Professionals

- Aptamer Biosensor Technology to Transform Virus Detection

- AI Models Could Predict Pre-Eclampsia and Anemia Earlier Using Routine Blood Tests

- AI-Generated Sensors Open New Paths for Early Cancer Detection

- Pioneering Blood Test Detects Lung Cancer Using Infrared Imaging

- AI-Powered Cervical Cancer Test Set for Major Rollout in Latin America

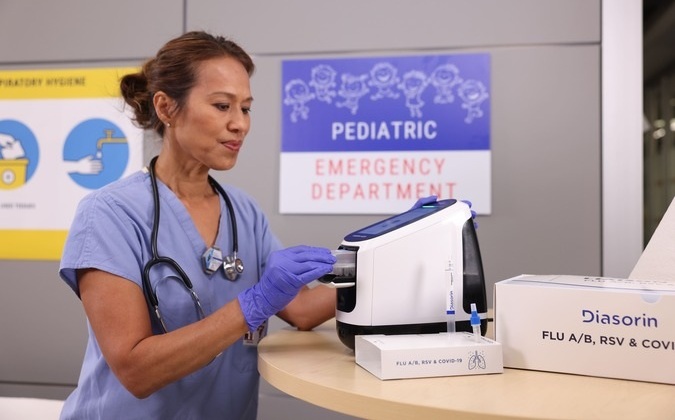

- Diasorin and Fisher Scientific Enter into US Distribution Agreement for Molecular POC Platform

- WHX Labs Dubai to Gather Global Experts in Antimicrobial Resistance at Inaugural AMR Leaders’ Summit

- BD and Penn Institute Collaborate to Advance Immunotherapy through Flow Cytometry

- Abbott Acquires Cancer-Screening Company Exact Sciences

- Gene Panel Predicts Disease Progession for Patients with B-cell Lymphoma

- New Method Simplifies Preparation of Tumor Genomic DNA Libraries

- New Tool Developed for Diagnosis of Chronic HBV Infection

- Panel of Genetic Loci Accurately Predicts Risk of Developing Gout

- Disrupted TGFB Signaling Linked to Increased Cancer-Related Bacteria

- First-Of-Its-Kind Test Identifies Autism Risk at Birth

- AI Algorithms Improve Genetic Mutation Detection in Cancer Diagnostics

- Skin Biopsy Offers New Diagnostic Method for Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Fast Label-Free Method Identifies Aggressive Cancer Cells

- New X-Ray Method Promises Advances in Histology

Expo

Expo

- Extracellular Vesicles Linked to Heart Failure Risk in CKD Patients

- Study Compares Analytical Performance of Quantitative Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Assays

- Blood Test Could Predict and Identify Early Relapses in Myeloma Patients

- Compact Raman Imaging System Detects Subtle Tumor Signals

- Noninvasive Blood-Glucose Monitoring to Replace Finger Pricks for Diabetics

- Blood Test Detects Early-Stage Cancers by Measuring Epigenetic Instability

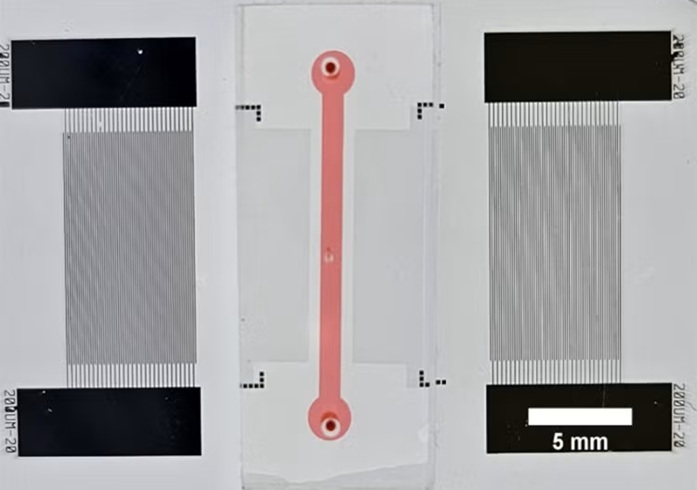

- “Lab-On-A-Disc” Device Paves Way for More Automated Liquid Biopsies

- Blood Test Identifies Inflammatory Breast Cancer Patients at Increased Risk of Brain Metastasis

- Two-in-One DNA Analysis Improves Diagnostic Accuracy While Saving Time and Costs

- Newly-Identified Parkinson’s Biomarkers to Enable Early Diagnosis Via Blood Tests

- Fast and Easy Test Could Revolutionize Blood Transfusions

- Automated Hemostasis System Helps Labs of All Sizes Optimize Workflow

- High-Sensitivity Blood Test Improves Assessment of Clotting Risk in Heart Disease Patients

- AI Algorithm Effectively Distinguishes Alpha Thalassemia Subtypes

- MRD Tests Could Predict Survival in Leukemia Patients

- Whole-Genome Sequencing Approach Identifies Cancer Patients Benefitting From PARP-Inhibitor Treatment

- Ultrasensitive Liquid Biopsy Demonstrates Efficacy in Predicting Immunotherapy Response

- Blood Test Could Identify Colon Cancer Patients to Benefit from NSAIDs

- Blood Test Could Detect Adverse Immunotherapy Effects

- Routine Blood Test Can Predict Who Benefits Most from CAR T-Cell Therapy

- AI-Powered Platform Enables Rapid Detection of Drug-Resistant C. Auris Pathogens

- New Test Measures How Effectively Antibiotics Kill Bacteria

- New Antimicrobial Stewardship Standards for TB Care to Optimize Diagnostics

- New UTI Diagnosis Method Delivers Antibiotic Resistance Results 24 Hours Earlier

- Breakthroughs in Microbial Analysis to Enhance Disease Prediction

- ADLM Launches First-of-Its-Kind Data Science Program for Laboratory Medicine Professionals

- Aptamer Biosensor Technology to Transform Virus Detection

- AI Models Could Predict Pre-Eclampsia and Anemia Earlier Using Routine Blood Tests

- AI-Generated Sensors Open New Paths for Early Cancer Detection

- Pioneering Blood Test Detects Lung Cancer Using Infrared Imaging

- AI-Powered Cervical Cancer Test Set for Major Rollout in Latin America

- Diasorin and Fisher Scientific Enter into US Distribution Agreement for Molecular POC Platform

- WHX Labs Dubai to Gather Global Experts in Antimicrobial Resistance at Inaugural AMR Leaders’ Summit

- BD and Penn Institute Collaborate to Advance Immunotherapy through Flow Cytometry

- Abbott Acquires Cancer-Screening Company Exact Sciences

- Gene Panel Predicts Disease Progession for Patients with B-cell Lymphoma

- New Method Simplifies Preparation of Tumor Genomic DNA Libraries

- New Tool Developed for Diagnosis of Chronic HBV Infection

- Panel of Genetic Loci Accurately Predicts Risk of Developing Gout

- Disrupted TGFB Signaling Linked to Increased Cancer-Related Bacteria

- First-Of-Its-Kind Test Identifies Autism Risk at Birth

- AI Algorithms Improve Genetic Mutation Detection in Cancer Diagnostics

- Skin Biopsy Offers New Diagnostic Method for Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Fast Label-Free Method Identifies Aggressive Cancer Cells

- New X-Ray Method Promises Advances in Histology